| The Courier - N°160 - Nov - Dec 1996 - Dossier Habitat - Country reports: Fiji , Tonga (ec160e) source ref: ec160e.htm |

| Country reports |

| Fiji |

Fiji

Political stability is the key to economic success

In most of the ACP states featured in our Country Reports, the vital issues are usually economic and social ones. How is a nation with a poor natural resource base to achieve lasting development ? What can be done to improve the skills of the people? How can a vibrant private sector be created ? Can better health care be delivered and how should it be paid for? Some of these questions might well be valid for Fiji but the visiting journalist soon discovers that they are all secondary issues. For this is a country whose political system itself dominates the agenda. The fundamental issue here is the relationship between the indigenous people of Fiji and the descendants of indentured Indian labourers brought in by the British between 1879 and 1916 to work in the sugar cane fields.

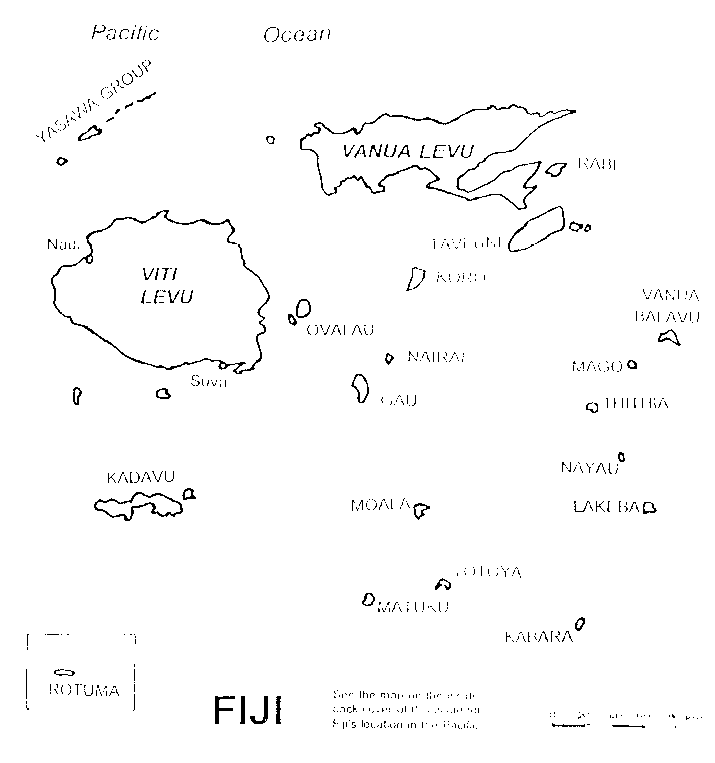

Fiji, in fact, is home to people of a variety of cultures. On the indigenous side, the majority are Melanesians but there are also some Polynesians (living on the island of Rotuma). The country even plays host to Banabans, from Kiribati, who were displaced from their homes on Ocean Island to make way for the phosphate diggers. They hold a freehold to the island of Rabi and enjoy a special self-governing status. And while the Indians form the bulk of the non-indigenous population, there are also small Chinese and European communities as well as a number of inhabitants of mixed race.

Despite this diversity, it would be inappropriate to describe Fiji as a melting pot. Ever since the rapid expansion of the Indian population, official policy has tended to accentuate the divisions. In the early days, it was the British who were responsible for this, although one has to be careful to avoid value judgments. The colonial administrators, it seems, were aware of the tensions that would arise by bringing in large numbers of people of a different culture, language and religion. Their eventual response was to provide guarantees for the local population, notably as regards land rights. The effect was to preserve the traditional land tenure system which was based on villages and families. At the time, it seemed a logical thing to do, but several generations on, the country now has a settled population of Indian origin (43% of the total) who have limited opportunities to own land - even though many of them work on it.

As the economy has developed, each of the two main communities has found itself 'specialising' in different fields. For example, cane farmers and retailers tend to be of Indian origin while the public service has traditionally attracted more native Fijians. Significantly, the army is almost exclusively filled by indigenous people - a crucial factor in the 1987 military coup.

On the political front, as Fiji moved towards independence, the idea of providing separate representation for each ethnic group also took hold. The independence constitution of 1970 reflected this with the two main communities being given parity (22 seats each) in the House of Representatives.

Shattered illusion

Although there was no real assimilation between 1970 and 1987, Fiji was seen by many as a model of a successful multiracial society. It was only when the country got its first Indian-dominated administration (sustained in power by a smaller native Fijian party) that this illusion was shattered. There was a military coup led by Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka, who is now the elected Prime Minister,. Shortly thereafter, Fiji became a republic (Queen Elizabeth was formerly Head of State) and in 1990, a new Constitution was adopted giving political primacy to the indigenous Fijians. Needless to say, it was a time of greatly heightened communal tension.

The 1987 coup and the events that followed have been well covered elsewhere (including our previous Country Report which was published in 1991). It suffices to say here that while the last few years have been a lot less turbulent, tensions remain. In 1997, the country must adopt a new set of constitutional proposals and a big debate is currently under way about the shape of the system of government for the 21st century. This subject is covered in a later article and also features prominently in our interviews with the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader.

The main focus of this article is therefore on economic and social aspects although, as one soon discovers, this frequently leads us back to the ethnic question. This is particularly the case when one considers the overall economic performance of the country. Fiji is not poor by developing nation standards and it has enjoyed modest growth during 1995 and 1996, but there is a widespread view that it could be doing a great deal better were it not for the political uncertainties. The problem is summed up by the Economic Intelligence Unit in its Fiji Country Report for the first quarter of 1996: 'Political instability will continue to deter investment, other than that on highly favourable tax terms.' In other words, Fiji is paying a high economic price for its internal difficulties.

General unease about the future and, in particular, the outcome of the constitutional review process is compounded by specific concerns over land tenure. The long-term leases granted to (mainly Indian) farmers are approaching their end and the government must soon decide what it should do next. Will any of the sugar cane farmers be evicted and if so, how many ? What alternative arrangements will be made for them? These questions remained to be answered when The Courier visited Fiji in July although, as our keynote interviews show, the subject was clearly exercising the minds of the politicians.

A long-term strategy for agriculture?

The way in which the land question is dealt with will have a crucial impact on the sugar industry - still the country's most important product in terms of its contribution to GDP and the jobs that it generates (see the article entitled 'Sugar definitely has a future'). With other uncertainties facing this sector - in particular, the process of global liberalisation - there is a growing recognition of the need for a long-term strategy. The government has a two-pronged approach - improving efficiency within the sector and diversifying into other agricultural products. To learn more about this, we spoke to Luke Ratuvuki, who is the Permanent Secretary for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests.

Mr Ratuvuki began by stressing the scope for increasing the sugar yield per hectare by as much as 75% (and by even more with irrigation). If productivity could be boosted on this scale, Fiji sugar would be in a much better position to compete in open world markets. He admitted, however, that the country would still face a struggle in maintaining market share and, looking ahead ten years, foresaw a slimmed down industry providing high quality sugar with more of a focus on niche markets. This inevitably meant looking at other agricultural products as possible long-term substitutes. The coconut (or as the Permanent Secretary dubbed it, 'the tree of life') is traditionally grown here and seems poised to enjoy a new lease of life following a period of decline. Fiji has also picked up the taro trade at the expense of Western Samoa, which is affected by taro blight, while there are significant exports of ginger to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Europe. Mr Ratuvuki spoke enthusiastically about branching out into other areas such as pawpaws, mangoes, bananas and aubergines.

Fiji has potential for growth in a range of non-agricultural sectors, but farming is sure to play a vital part in the economy for many years to come. Currently, sugar represents almost three quarters of all crops by value (excluding subsistence growing) and the Fijians are only too aware that this makes the country particularly vulnerable to external shocks.

The other primary sectors are all present in Fiji, albeit on a more modest scale. There is some deep-sea fishing backed by Asian investors. This provides useful employment although perhaps not the best possible financial return to the country. As one would expect in a nation of three hundred islands, there is also extensive artisanal and subsistence fishing in the inshore areas.

The forestry sector divides into two parts: artificial softwood plantations which are said to be managed sustainably and the naturally growing hardwoods. As regards the latter, the EU is helping with a mapping project. Although Asian loggers do not operate in Fiji, there is considerable land clearance taking place, leading to problems of erosion and silting.

Prospects for mining

Gold is the main mineral being exploited with important deposits around Vatukoula. The sector has had its ups and downs but the Emperor Gold Mining Company has now embarked on an expansion project aimed at raising production from the current level of about 4000 kilos per annum to 6000 kilos by the year 2000. A huge copper and gold mine is also planned for Namosi, some 35 km from Suva. Other minerals discovered but not exploited include bauxite, iron, lead, zinc, phosphates and marble. Mining currently makes a modest contribution to overall GDP but represents an important component in the export earnings figures.

With one key exception, manufacturing is on a fairly small scale with an emphasis on staple items (butter, beer, soft drinks, paint, soap etc.) for the local market. The exception is the garment industry which provides some 20% of the country's export income and a considerable amount of employment.

The investments in garment manufacturing and mining have been important in jobs terms and in improving the trade figures, but there are those who criticise the fact that the government appears to derive little revenue from the operations. The exact fiscal benefits are not easy to determine, prompting some observers to suggest that official secrecy should be eased (see the article on the Constitutional Review later in this Country Report).

In the service sector, long-term growth is foreseen in the key area of tourism. The number of holidaymakers choosing Fiji dipped sharply at the time of the coup, illustrating the importance of political stability in attracting visitors. Tourist arrivals bounced back once Fiji's internal difficulties had receded from the international headlines. The politicians must be hoping that nothing will occur during the current period of constitutional discussion and negotiation to put Fiji back on the front pages. It is worth mentioning here that Fiji's national carrier, Air Pacific, is an example of a relatively rare bird - an airline that makes money ! According to journalist Avin Rahish, writing in the July 1996 issue of The Review (the news and business magazine of Fiji): 'It is one of the few government investments that is profitable on its own.'

If tourism is a success story, there is something of a shadow over the financial services sector, which is more extensive here than in most developing countries. The reason is the collapse last year of the National Bank of Fiji with losses of US$ 142m (equivalent to 10% of the annual GDP). The authorities were accused of a failure in supervision and the taxpayers have had to pick up some of the bill. More serious, however, is the undermining of confidence in the system and it will take time for this to be restored.

Social challenges

As a middle-income country, Fiji has relatively favourable social indicators in the areas of health and education. Medical facilities are provided by the government but it is said that the public health system is not as good as it once was. This is attributed, among other things, to the emigration of highly qualified staff in the aftermath of the events of 1987. Nonetheless, the country does have 27 hospitals and one doctor for approximately every 1900 people. At 72 years, life expectancy is high compared to the ACP average.

The education sector is well-developed with more than 800 primary and secondary schools (for a population of less than 800 000) and 41 technical or vocational institutions. As a result, primary school enrolment is close to 100% while the 1986 census revealed that 60% of 15-year olds were still in education. On the other hand, there are concerns over the proportion of teachers lacking qualifications, notably in the primary school system. In practice, there is considerable racial segregation at both primary and secondary levels, although there is no official policy to this effect.

Educationally, the jewel in the crown is almost certainly the University of the South Pacific whose main campus is in Suva. This regional institution, which has departments in a number of other countries of the South Pacific, draws students from various island nations. Dr Vijay Naidu, who is the USP's Pro-Vice Chancellor, outlined some of the special features of this unique university which has to cater for a highly dispersed population. Like traditional tertiary institutions, it provides a wide range of degree programmes on campus, catering for 3500 students. It has a further 9000 who are being educated using the 'distance mode'. Distance learning is organised through centres in each of the participating countries. Students can attend these centres from time to time but much of their work is done through radio and telephone linkages and, increasingly nowadays, by e-mail and satellite communications. The University, Dr Naidu stressed, also provides continuing education at non-degree level 'in everything from computing to basket-weaving'.

Like the health sector, the USP suffered a loss of highly qualified staff after 1987 - and not just among employees of Indian origin. As the Pro-Vice Chancellor pointed out, the coup created 'a new sense of insecurity' all round and teachers who decided to emigrate were quickly accepted in Australia and New Zealand. The loss has been particularly serious in the scientific disciplines.

90% of the USP's recurrent expenditure is covered by member government contributions with the remainder coming from Australia and New Zealand. For capital investments, there is heavy reliance on external donors.

In both of Fiji's main ethnic communities, a strong commitment to the family ensures that there is relatively little absolute poverty although things may be changing as the country become more urbanised. It is rare to see beggars in the streets in the South Pacific but Suva, sadly, has a number of these.

The overall picture is of a country with very considerable potential in both human and natural resource terms which needs to overcome a number of challenges to secure a more prosperous future. Some of these challenges - adapting to the world of free markets, tackling bureaucratic impediments, bringing development to rural villages, improving the infrastructure, and so on - are familiar to all developing countries. The single most important constraint, however, is the big ethnic divide, and the political uncertainty which flows from this. And this is something which can only be solved by the people of Fiji themselves.

Interview with Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka

'The last ten years have been very educational for me'

It is almost ten years since Sitiveni Rabuka led the military coup which toppled the newly-electerl coalition government The stormy events of 1987 are long gast end Fiji has returned to more peaceful ways, but the country is arguably not yet at peace with itself. Major-General Rabuka is now the erected Prime Minister, having led the SVT to victory at the polls in 1992 and 1994. But the gulf between the native Fijians end citizens of Indian descent remains - indeed, it is institutionalised in a political system which ensures a parliamentary majority for the former. A constitutional review is currently under way end a new text must tee adopted by July 1997. For both sides, the stakes are high. In this interview, Prime Minister Rabuka speaks frankly about the crucial issues facing Fiji as the nation gears up for the great constitutional debate.

Fiji also faces some formidable economic challenges and we began by asking the Prime Minister about these.

- The main challenge is the one that everybody faces: achieving an acceptable rate of growth to ensure job creation and address the unemployment problem. We also want to improve the standard of living of the people, to upgrade our infrastructure, and to develop both the urban and rural areas.

· What sectors do you see as offering the best hope for future growth ?

- We are looking particularly at tourism and the agro-based industries. In the international sphere, we are aiming to boost trade, particularly with our traditional trading partners, Australia and New Zealand, and with new partners that we are trying to cultivate in Asia.

We are very grateful for the Lomé Convention and the various arrangements associated with it - particularly as regards access to the EU market for our sugar products. Although it would be desirable for us not to have to rely on preferential pricing for sugar, for the moment, there is no alternative. And while we are looking for alternatives and seeking to diversify our economy, we will need that system to remain in place. We would like to continue the dialogue to ensure that this happens.

In the area of trade, as I say, our focus is on Australia and New Zealand, and the regional trade agreement that the Pacific island territories have with them. This agreement is currently under review. One important aspect is the clause governing the rules of origin. If we can convince Australia and New Zealand to reduce the local input requirement from 50% to 35%, then we won't need any aid from them. The effect will be to secure existing jobs and, indeed, to increase employment, particularly in the garment industry. At the moment, most of the textiles we import for further processing come from Australia. Because of the market we have to sell to, it is very good quality material. This means the costs are high, in comparison with the local input needed to turn it into finished products, and this makes it difficult for us to get up to the required 50%.

If we don't get that reduction, things could go in the opposite direction. Manufacturers might relocate and we could be facing jobs losses. You have to remember that we are competing with Asian producers who have very low wage costs.

· Is this proposal for a reduction in the local input requirement on the agenda with the Australians and New Zealanders ?

- The review actually excludes the clause on the rules of origin. Having said this, we have effectively raised the calculation of our local input in negotiations on a series of other points. On paper, the 50% figure is unchanged but in fact, there has been a reduction of about 5%, thus giving us a little margin.

· On the sugar issue you said you were hopeful that some form of preferential access to the EU market would be maintained. Isn't there a concern that this may not last beyond the year 2000, particularly given the increasingly liberal world trading system ?

- Yes, and we are looking at that. We should be gearing ourselves up for what happens at the end of the current Lomé agreement. It remains to be seen whether, with the WTO and the new trends, the curtain will suddenly be brought down on 1 January 2000, or whether there will be a grace period in which we are given time to consolidate our diversification.

· The other big issue in the sugar sector concerns the impending expiry of the land leases.

- That is a local issue and a very important one. It has high priority on our government agenda. We are currently talking to the landowners and lessees, explaining what will happen. The legislation (the Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Act) makes no provision for further extensions to the leases, which are now nearing their end. Do we need a new act or should we amend the present law to allow extensions beyond the 50 years originally allowed for ? And if we are to do that, what happens to the compensation provisions? At the moment, these are viewed in a rather one-sided way. The emphasis is on the situation where the landlord compensates the tenant for improvements made to the land. But the rules also provide for compensation in the other direction where the value has been reduced. This may be due to constant cultivation over 50 years. What if the owner wants to return the land to its original use, planting taro, yams or cassava, as his father may have done fifty years ago, and finds he can no longer do so ? There has to be a balancing act here.

Hopefully, most of the land will be leased again under a new agreement or under an amendment to the existing law - because we will need to continue sugar production. It is also worth noting that some sugar farmers are beginning to diversify into other crops, both subsistence and commercial.

· What arrangements do you envisage for those farmers who do not have their leases renewed ? Will they be relocated ?

- Right now, we are looking at the use of state land. There are two basic categories here - what used to be known as 'Crown Land under Schedule A' and 'Crown Land under Schedule B'. Schedule A covers the land not claimed by anybody during the Commission that was set up to determine the ownership of land in the very early colonial years. Schedule B is land that belonged to a community or landholding unit that has since died out: in other words, where there is no surviving member of the land-owning unit. So we have those parcels of land available. My party's policy is to restore land to the traditional owners where possible, but in those cases where you cannot identify the original owners, there will be land available for resettlement - although resettlement is perhaps not a very good term to use.

· It is somewhat emotive.

- It implies taking a person, family or community from somewhere and planting them somewhere else - and I hope we can avoid that. On the other hand, if you look at what people are doing nowadays, everybody's relocating. People are always resettling, moving away from home and setting up elsewhere. In this case it is perhaps a necessity, in the sense that the legislation has caught up with us.

· Can I turn now to the sensitive issue of the constitution. This is another area where decision day is looming. You currently have a constitutional review under way with the Commission's report due out soon. What do you think will emerge from this process over the next 12-18 months ?

- I don't feel that the constitutional issue is a sensitive one and do not think anyone should feel restrained in asking questions about it. It reflects the reality of the situation in Fiji. There is a requirement that the 1990 Constitution be reviewed and we have a Review Commission chaired by Sir Paul Reeves. He is a very capable man who is a former Governor-General of New Zealand and a very eminent constitutional lawyer. Assisting him, we have two party nominees - one from the main Fijian party and one nominated jointly by the Indian parties in Parliament. I have total confidence in that Commission. I believe they will come up with very objective observations and recommendations.

Let me explain the timetable to you. The report is expected by the end of August. It will be presented first to the President and then to me for submission to Cabinet. I envisage it being tabled in Parliament towards the end of September. We cannot debate it until three months have elapsed from the date it was tabled - which takes us to the end of the year. A lot of work will be needed during the first half of 1997. The Joint Parliamentary Select Committee, made up of members of both the upper and lower houses, will have to work on the report and try and build consensus on the various issues.

Given that the house is racially divided, and the possibility that a premature discussion on the floor of the house may raise the temperature, I would prefer not to have a full parliamentary sitting in the early part of next year. Instead, we should go into committee and deal with it there. And then when we are satisfied that the issues can be brought out into the open, we will debate them fully in Parliament. As soon as we start talking next year, the legislative craftsmen should begin their work. On the basis of this programme, I believe we can meet the deadline to the day, promulgating a new Constitution which has been accepted by both houses on 25 July 1997. So I am very hopeful.

· Without prejudging the final outcome, do you envisage a move away from strict communal separation ? I am thinking here, in particular, of the separate voting lists ?

- I think there may be provision for some cross-communal voting. There was something like this in the 1970 Constitution which had both communal and national rolls.

· What about the longer term. Do you foresee a political system developing in Fiji where ethnic origin is irrelevant - perhaps a 'right-left' divide, if that is still a meaningful concept ?

- I am not bold enough to say that that will happen. I have seen the darkest side of Fijian nationalism. I have seen the fear that was in the Indian population in 1987. But if we move too quickly to remove the racial safeguards that are in the Constitution, we may run the risk of prolonging the bad relationship between the races that we now have. So I would say we should proceed very cautiously and let the natural healing process take its course. We also need to look beyond the Constitution at aspects such as our education system and enhancing the ability of the Fijians to compete.

· I believe the education system is also very divided.

- Some schools are reserved for Fijians although, slowly, there are Indians from families close to the schools who are beginning to enter them.

· Do you think that this is a promising sign for the future ?

- I think so. I went to a purely Fijian school and when I came out of that, everything was Fijian for me. I went straight into the army which is another Fijian-dominated institution. It was not planned that way. It is just the way it happened. My tolerance level of other races was very low. But you cannot expect somebody who gets to this level of leadership to have a low racial tolerance level. I must admit that the last ten years have been very, very educational for me - very good for my own being. I consider what I used to think before and the way I used to feel before. I have never been threatened by an Indian, but I had always been in Fijian 'safe' areas - a Fijian school and then in the army. But since coming out of that sort of cocoon, I have managed very well to accept that I have to compete with them, I have to look after them, and I have to devise policies and programmes that will be good for them as well as being good for us.

· One final question. Do you envisage Fiji seeking to rejoin the Commonwealth in the near future ?

- I think seeking is the wrong word. We will do what we feel is good for Fiji and its people. The people of Fiji are those who are here now but it will include some of those who have moved on looking for greener pastures and who are willing to come back. We were not expelled from the Commonwealth; our membership lapsed. It is up to the Commonwealth to say whether they are prepared to reconsider our member ship.

Profile

General information

Area: 18 272 km². Fiji has two main islands (Viti Levu and Vanua Levu) and about 300 smaller ones. It has an Exclusive Economic Zone of approximately 1.3 million km²).

Population: 790 000

Population density: 43 per kilometre²

Capital: Suva (situated on the island of Viti Levu)

Main languaqes: English, Bauan

(main Fijian language)

Currency: Fiji dollar (F$). In June 1996, 1 ECU was worth approximately F$ 1.80. (US$1 = F$ 1.40)

Fiji

Politics

System of government: A bicameral parliamentary system consisting of an appointed Senate and an elected House of Representatives. The President is a non-executive head of state chosen by the Great Council of Chiefs. The President appoints the Prime Minister.

Under the Constitution, adopted in 1990, the Parliament is divided along racial lines. The Senate has 34 members, 24 of whom are indigenous Fijians. In the 70-member House of Representatives, 37 seats are reserved for native Fijians, 27 for Indo-Fijians, 5 for 'general voters' (other ethnic groups) and 1 for Rotuma Island (whose inhabitants are Polynesian). The 1990 Constitution provides for a review within seven years and discussions are currently under way with a view to amending the Constitution by the 1997 deadline.

President: Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara

Prime Minister: Major General Sitiveni Rabuka

Main political parties: Soqosoqo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT - Fijian), National Federation Party (NFP - Indian), Fiji Labour Party (FLP - Indian), Fijian Association (FA - Fijian), General Voters Party (GVP).

Party representation in Parliament (1994 election result): SVT 31, NFP 20, FLP 7, FA 5, GVP 4, Others 3.

Economy

GDP: (1995) F$ 2.85 billion

Annual GDP per capita: approx US$ 2600

GDP growth rate (1995): 2.2% (2.9% predicted for 1996)

Principal exports (1994): Sugar (US$ 182m), Garments (US$ 96m), Gold (US$ 43m), Fish (US$ 38m), Timber (US$ 21 m) Main trading partners (in order of importance):

Exports - Australia, UK, USA, Japan, New Zealand.

Imports - Australia, New Zealand, USA, Japan, Singapore.

Trade balance (1994): exports - US$ 547m, imports - US$ 826, deficit - US$ 279m. The current account figures also usually reveal a deficit but this is much smaller due to tourism earnings and official transfers.

Inflation rate (1995): 2.2%

Government budget (1996): revenue - F$ 759m, expenditure - F$ 851 m, deficit - F$92 (about 3.5% of GDP)

Forma/sector employment: 98 112 (out of a total economically active population of about 265 000)

Social indicators

Life expectancy at birth (1993): 71.6 years

Adult literacy (1993): 90.6%

Enrolment in education: all levels from age 6-23: 79%

Human Development Index rating: 0.853 (47th out of 174)

Sources: Economic Intelligence Unit, UNDP Human Development Report, 1996, EC Commission.

An interview with opposition leader Jai Ram Reddy

'We need to move to a more racially neutral system'

Fiji is not unique in having a political system that is heavily influenced by racial or communel issues In places as diverse as Northern Ireland, Belgium, Guyana and Trinidad - not to mention many parts of Africa - people vote for parties which claim to represent the particular ethnic, religious or linguistic group to which they belong. Where Fiji is different, however, is in having a Constitution that gives primacy to one particular community. Since the 1987 coup, native Fijians have held the upper hand with a guaranteed majority in Parliament and a firm grip on the levers or power.

The 1990 Constitution, adopted when communal feelings were still running high, contained a requirement for a constitutional review within seven years. When The Courier visited Fiji (July 19961 the work of a three-member Commission appointed to carry out the review and make recormmendations was nearing completion. All sides seem to accept the need for reforms designed to help bridge the sharp racial divide.

The big question is how radical these reforms are likely to be. We sought the views of Jai Ram Reddy, the leader of the opposition National Federation Party (NFP) which has the support of most of the country's Indian (Indo-Fijian) community.

· You are the first opposition leader I have met who cannot, constitutionally, become Prime Minister. How do you feel about that ?

- It is something that rankles with me - the mere thought that I am not equal with my fellow citizens of other races. I think that's generally the way the Indians feel here. All the constraints and limitations, the denial of basic human rights, are the source of a great deal of unhappiness.

· You talk about basic human rights. Obviously, the political aspects are very important but I get the impression that, in other respects, this is a fairly free and easy society: there is free expression, for example.

- Yes, but free expression is only one aspect of human rights. The fact is that discrimination based on race is widespread and institutionalised. About 45% of the population is Indo-Fijian but you will find they are not fairly represented in the higher levels of the public service. At the Permanent Secretary level, there is definitely a government policy to have a limited number of Indians - and there are hardly any in the more crucial ministries. The same is true of managerial positions throughout the public sector. In the statutory bodies and major public undertakings, there is a deliberate policy of excluding Indians. So we are very much a marginalised community in the public sector.

· Wouldn't it be true to say that Indians have quite a lot of economic power ?

- No, I don't agree. There is a tendency for people who come here, end for some people in Fiji, to project this image of Indians controlling the economy. It is a fallacy. It all boils down to how you define economic power.

Let's take natural resources. The land, and therefore the forests, are almost exclusively owned and controlled by native Fijians. Even in the corporate sector, the largest business undertaking is the manufacture of sugar, and 80% of the shares are owned by the government. The Indians don't own this industry. They are the small sugar cane producers working on ten-acre plots. And who controls banking and insurance ? Certainly not the Indians. Most of the financial services companies are foreign-owned.

The area where the Indians are most visible is in the retail sector. But those little shops you see in the towns are small family businesses. The shopkeepers work up to 15 hours a day, and you will discover that many of them do not even own their premises; they are tenants. So the idea that Indians control the economy is a bit of a myth.

· The Constitution, and in particular the system of racial differentiation for voting and holding certain offices, is obviously a key issue for you. With the Constitution currently under review, what is your party's policy in this area ?

- The first elections under the current Constitution took place in 1992 and we took part in them under protest. We made clear that our participation should not be construed as acceptance of the system. Indeed, the sole issue on which we campaigned was our rejection of the Constitution. But we accepted the fact that we needed to get into the system as it was, and to try and create an environment where there would be widespread appreciation that it had to change. The 1990 text, in fact, laid down that it had to be reviewed by the seventh anniversary of its promulgation. I think the architects of the Constitution realised themselves that it was deficient. And we laid great emphasis on the need for dialogue; a general recognition that the country would be much better off with everybody working together and that there was nothing to be gained by oppressing or marginalising a community. And that is the kind of environment we have tried to create.

· The Constitutional review will shortly be published. What do you hope will come out of that exercise ?

- I am reasonably optimistic. I think the environment is more favourable now and there is a general recognition that the system has to change. I am sure you will get confirmation of this when you talk to the government side. We need to move away from this very polarised, compartmentalised political system to a more racially neutral one. I think views may diverge as to how far we should go. That will be the contentious issue. But I believe we will make progress.

I certainly think we will get a good report from the Constitutional Review Commission. One of our fears, when we started on this journey, was whether it would be independent and be given fair terms of reference. Largely because of the cooperative and accommodating attitude that we ourselves adopted, and to which the government responded, we were able to get a Commission that was well-balanced. We are very fortunate to have Sir Paul Reeves, a former Governor-General of New Zealand. His independence is taken for granted. The Commission also has one nominee from the indigenous side and one from the Indo-Fijian side. So we certainly expect a good report. There is already a kind of acceptance I think on all sides that political parties need to prepare themselves for a more multiracial approach to governance in the future.

· On this point, I see that the SVT (the governing party) is looking at the idea of opening up its membership to other groups.

- That's right.

· Do you think there will be many nonnative Fijians interested in joining ?

- Not straight away but at least it is a beginning. It is an acceptance that they can't remain racially exclusive. If, for example, the Commission recommends a move toward a racially neutral system - at least for a certain number of seats - then it would be important for the SVT to have non-Fijians in their party.

· Can I turn to economic issues, which I presume cannot be divorced altogether from political ones ? There is a lot of discussion about the future of the sugar industry which is tied in with the question of renewing the land leases This is an issue which is due to be resolved soon. How concerned are you about the impending decision on the leases ?

- This is something that concerns us very deeply. As you correctly observe, you can't separate the political and economic aspects. The two are very closely interlinked here - perhaps more so than in other countries - because of the land situation. The bulk of Indian peasant farmers, both within and outside the sugar industry, are on leases that will begin to expire next year. If these are not renewed, the problem will not just be an economic one but an enormous human one. What do we do with these people who all belong to a particular racial group. It really boils down to our very survival. Despite the growth in the towns, the bulk of the people are still rurally based. They are small subsistence farmers, living in the country areas with no more than 10 or 12 acres to cultivate. So the social implications of non-renewal in terms of poverty, dispossession and hardship are enormous.

· But how real is the concern ? Surely, the overwhelming economic logic is for the leases to be renewed. After all the land is being put to productive use at the moment

- Yes, but unfortunately, when you have a communal dimension to the problem, logic does not always prevail. If you think about it, there was no logic in the events of 1987. The trouble is that every issue here has a racial twist. After the coup, communal sentiments were aroused and sharpened. There was a prolonged period of anti-lndian propaganda and in that environment of anger, a highly racial constitution was adopted. There were people in positions of influence openly advocating non-renewal, threatening to take all the land back. Now they need to undo all this and it will not be easy, given the enormous strength of feeling that has been aroused. Having said this, I believe that we are now in the process of restoring sanity to our public life. It is also beginning to dawn on everybody that the sugar industry is vital for Fiji and it will continue to be so for some years to come.

· I have heard that view expressed on all sides, but I wonder if people are sufficiently aware of the implications of global liberalisation. It has been suggested that this will make sugar increasingly unviable.

- I think a lot of people are unaware of the implications, because there has been very little public education in this field. But amongst those 'in the know', there is certainly an appreciation. I am a member of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Sugar and we were recently addressed by the head of the marketing company and the head of the Sugar Commission. At that level, there is an awareness, but if you speak to the average farmer who has been growing and selling sugar for many years, he will probably assume that life will just go on as before.

Isn't it true to say that sugar depends heavily on the Lomé Convention arrangement with the European Community ?

- Very much so. In my view, the sugar industry is run so inefficiently that but for the huge subsidy we get from the European Community, it would not be viable.

Presumably, this means that measures must be taken to improve efficiency ?

- Yes, absolutely. But the first issue to resolve is the land question.

There is no point talking to the farmers about efficiency - asking them to improve their husbandry and focus on sugar content rather than the quantity of cane produced - when they don't know if they will have land to cultivate after next year. So you see all other issues have become completely subsidiary to the tenure question. At the moment, we are in a limbo. The government and the people urgently need to resolve this problem. Then we can put it behind us and address the other concerns.

Are there any other economic sectors which you feel offer promise for the future of the country ?

- Any growth outside of tourism will, I think, have to be centred on the agricultural sector. We need more agro-based industries and more diversification. We could grow a lot of other crops here - mangoes for example. We also need to improve extension services to farmers, and make an aggressive effort to identify markets. The farmers will grow the crops but they must be sure that somebody will buy them. Every year, for example, we have a glut of tomatoes - so many that they can't even give them away in the markets. This kind of problem kills the incentive to produce.

There is obviously heavy state involvement in the running of agriculture. Do you see scope for more privatisation or 'corporatisation' in line with global trends ?

- I think that growth, even in the agricultural sector has to be private-sector driven. At the same time, you have got to create the right environment and infrastructure for this to happen. Unfortunately, it keeps coming back to this question of land. If big investors, for instance, want to come here and invest in agriculture, they need to know what sort of tenure they are going to get and whether they can buy the freehold. I am sure there are people, particularly now from the Asian region, who would be interested in investing in agriculture, but the land problem is a big constraint.

Do you think Fiji will rejoin the Commonwealth at any point ?

- Well, we hope so. You know we are all very strongly in favour of rejoining. One of the things that I personally feel very strongly about is the unfortunate severance of our link with the Queen. I don't know, constitutionally, whether it can be restored. Obviously, there are difficulties in that area, but I think a large majority of ordinary people in this country would like at least to see Fiji back in the Commonwealth.

Seeking a lasting constitutional settlement

When The Courier visited Fiji in July, the report of the Constitutional Review Commission headed by Sir Paul Reeves (former Governor-General of New Zealand) had not yet been completed - and what it would contain was a major topic of speculation. As readers will see from the interview we publish with the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader, the impartiality of the three-member Commission was not in question - at least within the political mainstream on both the native Fijian and Indian sides. Nonetheless, there were doubts about whether a consensus could be found. For the Indo-Fijians, a scaling down of the 'racial' features in the Constitution was seen as a prerequisite. Yet the ruling SVT, in its own submissions to the Commission, had effectively supported the status quo. In view of this apparently unbridgeable gulf, could the compilers of the Report come up with recommendations capable of forming the basis for a lasting constitutional settlement ?

The long-awaited Report was formally transmitted to President Ratu Mara on 6 September and a few days later, it was tabled to a joint session of the Senate and the House of Representatives. It now falls to a joint select committee of the two Houses to thrash out a new set of constitutional proposals. These will be presented to Parliament for debate and decision in the first half of next year with a view to meeting the July 1997 deadline foreseen in the 1990 Constitution.

The Report of the Review Commission is lengthy (almost 800 pages) and contains no fewer than 697 separate recommendations. The key ones, however, relate to the system for electing members of the House of Representatives. Currently, separate electoral lists based on race are used to fill all 70 seats (37 native Fijians, 27 Indo-Fijians, 1 Rotuman and 5 'General Electors', covering all other races). It was widely expected that the Commission would propose a mixture of 'reserve' seats and 'open' ones, with the latter, as their name implies, being chosen by the whole electorate.

45 'open' seats proposed

This is precisely what they have done - but the suggested breakdown may have come as a surprise to some. The proposal is for 45 open seats (15 three-member constituencies) and 25 single-member 'reserve seats (12 native Fijian, 10 Indo-Fijian, 1 Rotuman and 2 'General Electors'). If adopted, the new system would no longer legally guarantee a majority for people of Fijian origin in the country's legislature. What would happen in practice would depend on a number of factors including the nature of the voting system in the three member open constituencies, the willingness of people to cast their ballots across the ethnic divide and the actual turnout of voters from the different communities. It should be pointed out, however, that native Fijians now constitute half the population, large numbers of Indians having emigrated over the past nine years. So long as communal voting patterns persist, this will presumably be reflected in the Parliamentary arithmetic.

It is also proposed that the bulk of the 35-member Senate (Bose e Cake) should be made up of elected representatives of Fiji's provinces. In the field of local government, it is suggested that the present system based on villages and provinces, which applies only to native Fijians, might be replaced by an arrangement applicable to all races. In this context, the rote of the Council of Chiefs (Bose Levu Vakaturaga) would be reduced.

Although the sections of the Report relating to representation are bound to attract most attention, the Commission also put forward a series of other proposals aimed at improving the governance of Fiji. One idea, which appears designed to alter the political culture, is for the 'Official Secrets Act' to be replaced by a 'Freedom of Information Act'. The presumption of secrecy would be replaced by a rule that official information should be accessible to the public except where there is good reason to withhold it. In a similar vein, the Report recommends an 'integrity code' to govern the behaviour of holders of public office.

Initial reactions to the outcome of the Commission's work were mixed. Key players, including the President, Prime Minister and opposition spokespersons broadly welcomed the Report but more nationalistic elements were quick to reject it and one group even mounted a ceremonial burning of the document.

It is obvious that a great many more words will be exchanged - and some of them will no doubt be heated - in the coming months. It is difficult to see how everyone can be 'brought on board' but the hope must be that a compromise can be crafted that is acceptable to the majority on both sides of the communal divide. The people of this Pacific island nation are well aware that prosperity and stability go hand in hand. The single most important achievement in ensuring stability for the longer term would be to secure a satisfactory settlement of the constitutional issue.

'Sugar definitely has a future'

This was the key sentiment expressed by Isimeli Bose, Fiji's Trade Minister, when he spoke to The Courier earlier this year. Mr Bose insisted that 'no matter what anybody says, sugar will be the backbone of this country's economy for years to come.'

When we discussed Fiji's current economic situation and future prospects with the Minister, it was not surprising that sugar should have featured so prominently. The sector faces a difficult future for both internal and external reasons. At home, the long-term leases granted to the farmers (mainly Fiji Indians) under the Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Act are due to expire over the next few years. No provision was made for their renewal and the resulting uncertainty has provoked widespread concern, not least among the leaseholders themselves. The external 'threat' comes from new international trade rules administered by the World Trade Organisation. At present, Fiji's sugar industry is heavily dependent on the preferential access to the EU market which was granted under the Lomé Sugar Protocol. No one is quite sure what will happen when Lomé IV expires at the turn of the century but it is clear that the stakes are high.

Mr Bose was quick to acknowledge the importance of ending the uncertainty facing the sugar farmers. 'But the real challenge', he said, 'is to ensure the maintenance of our markets for sugar.' He was aware of the encroachment of global trade liberalisation but stressed that the industry's leaders and the government were 'doing the work now and planning for the future.' At the same time, the authorities are clearly hoping that the European Union will be able to continue with some form of preferential arrangement after the year 2000, if only to buy time so that the industry can adapt and farmers can diversify.

On the subject of trade diversification, Mr Bose pointed out that 'the field is very limited'. He continued; 'However, since 1988, we have seen garment production picking up from very humble beginnings. By 1995, we had about F$185 million-worth of exports in this area.' He also spoke enthusiastically about the government policy of encouraging manufacturing in tax-free factories and zones. 'This developed well between 1989 and 1992 and then there was something of a slowdown.' Tax-free factories have been established in a number of locations and the first real tax-free zone is now being set up in Kalabo. Mr Bose indicated that EU assistance was being provided in this area.

Privatisation

Our conversation then turned to the changing economic role of governments - throughout the world, they are withdrawing from active involvement in industrial and commercial operations. We asked how far this process had occurred in Fiji and, in particular, whether there was a privatisation policy. The Minister replied in the affirmative, pointing out that government departments 'do not usually make very good businesspeople.' The policy, therefore, was to 'corporatise' and 'privatise', although the process is still in its early stages. The Trade and Commerce Ministry has a public enterprise unit which is responsible for drawing up a policy framework for the government. In 1995, Mr Bose explained, a public enterprise bill was presented to Parliament, 'but there were so many concerns expressed to the previous Minister that it was referred to a select committee - which, in fact was chaired by me before I took up my present poet.' The committee had now completed its work and the Minister indicated that the issue would go back to Parliament in September.

Despite the legislative delay, Mr Bose was keen to stress that his department was already working on individual programmes. The post and telecoms business, for example, had just gone through another stage towards privatisation.

There is, of course, an important distinction between 'corporatisation' and 'privatisation' - the former implies staying within the state sector but at arms-length from the administration. This point was acknowledged by our interviewee who explained that the approach was a step-by-step one. The first stage was to reorganise a department along commercial lines. Corporatisation came next 'and then finally you have privatisation by disposing of shares.'

He stressed that the most important aim was to ensure an element of competition wherever possible. 'There is no point simply moving from a government monopoly to a private monopoly', he insisted, 'although obviously, there are utilities like water, electricity and even telephones where this may not be easy.' The minister concluded; 'Where they are natural monopolies, we will regulate them.'

Our final topic of discussion was the possibility of regional integration in the Pacific.

How far had the South Pacific countries gone in this direction and did the Minister think there was a need for closer economic cooperation? Mr Bose replied that he thought economic integration was a good thing. He pointed to a document on his desk containing a draft proposal for a bilateral trade agreement with Papua New Guinea. 'We will soon be holding negotiations with them, and have also just signed an agreement with Tonga.'

The focus on bilateral trade arrangements at this stage suggests that the region still has some way to go on the regional integration path.

But the Minister nonetheless insisted that it was something 'that can and will happen'.

Our daily bread - courtesy of a remarkable Fijian businesswoman

How can a businesswomen succeed in Fiji's patriarchal society? Mere Samisoni, the entrepreneur behind the 'Hotbread Kitchen' gave us an appropriate answer when she said 'I roll with it', although the pun was probably unintentional In fact, it is difficult to imagine this dynamic lady being pushed around. Anybody who manages to build up a chain of bakeries from scratch, capturing 35% of the country's urban consumer market in the process, must have a lot of determination. At the same time, Mrs Samisoni displays a strong sense of social commitment. She believes in community values, advocates group decision-making and consensus, and even describes the tax system as 'reasonably fair'. In short, she contradicts the widely-held view propagated by lurid American TV series, that a dogeat-dog attitude is needed for business success.

In fact, Mrs Samisoni started out with the idea of working with one of the caring professions. Trained in nursing administration in Australia and New Zealand, she returned to Fiji only to find that there were no openings available. That was when she decided to go into the private sector, establishing 'Samisoni Enterprises'. And over the years, she has succeeded in building up one of the largest bread-making operations in the country. The Hotbread Kitchen operation is highly decentralised with the bread being baked in different locations for sale through the company's local outlets. Her business is also the first Fijian one to franchise out its operations. And having already won a big chunk of the urban market, she is now looking to expand operations in the rural areas.

Samisoni Enterprises, of course, is not simply a bread-making operation. The company now offers a line of 62 separate bakery products, with some local adaptations to suit varying tastes. It employs some 275 staff with perhaps another 50 working in the related franchise operations. And the business had an important breakthrough when it won the contract for 'MacDonalds' in Nadi. With branches of the famous hamburger chain likely to open in other parts of Fiji, this could be the start of something big. In fact, there is even a suggestion that Fiji could be used to source Macdonalds' operations in New Zealand, the rolls (or buns, as the Americans like to call them) being exported frozen.

Constant quality

For Mrs Samisoni, the key to a successful and profitable operation is 'constant quality' and unfailing attention to customer service. As she puts its, 'if you let quality slip just once, you can end up losing customers for a very long time.' Baking is a labour-intensive business and she is keen to stress the importance of developing people's abilities - in particular, the human relaitons skills of those who deal direct with the customer.

As if running a business wasn't enough, Mere Samisoni is also busy completing a Masters in Business Administration (MBA) at the University of the South Pacific, with a thesis on indigenous business. From what we discovered, speaking to this remarkable Fijian entrepreneur, she should have been helping to teach the course!

Viti Levu - island of contrasts

Anyone from overseas who is travelling to the Fijian capital, Suva, will soon discover that the country's largest island is a very diverse place. Roughly circular in shape, Viti Levu provides more than half of Fiji's total land area and is home to about three-quarters of the population.

The journey to Suva on the south-east coast will almost certainly involve transiting through Nadi International Airport (pronounced Nandi) which is situated in the west. This is the country's only major international gateway and while it is ideal for tourists heading for the resort hotels, it is less convenient for business travellers whose destination is Suva. Their journey has to be completed either by road (which takes several hours) or on one of the small commuter planes which ply regularly between Nadi and Nausori (itself a half-hour drive from the capital).

The biggest surprise to those who are unfamiliar with the country is that the west and the south-east have very different weather patterns. When your aircraft lands at Nadi, the chances are high that the sun will be shining. On reaching Suva, you are more likely to encounter rain. This part of the country enjoys - if that is the correct term - a micro-climate which is good for tropical vegetation but less appealing to human beings. The 'blame' for locating the Fijian capital in such a spot is said (not too seriously) to lie with the country's former colonial rulers. According to the story, a British envoy visited Suva on one of its rare sunny days and, on the strength of this, designated it as the seat of administration. The British can hardly deny their involvement since it was in 1882, during the early years of colonial rule, that the capital moved from Levuka (situated on the much smaller island of Ovalau). But the key reason was almost certainly the fact that Suva, with its large bay, could be developed as a port. Whatever the explanation, one must have some sympathy with the foreign diplomats who keep a raincoat or umbrella to hand at all times, and yet are viewed with envy back home because they have a 'paradise' posting.

To be fair, Suva has attributes other than its weather which make it an interesting place. It has, for example, some very attractive architecture, both local and colonial. The views across the bay can be dramatic - and, in this respect, the rolling cloud formations may actually enhance the picture. And the centre of the city buzzes with activity (except on Sunday because of the Sabbatarian influence).

The population of the greater Suva area is about 160 000. This may not be enormous, but it is the largest concentration of humanity to be found between Hawaii and Australia. In some ways, it is the 'capital' of the South Pacific - a point which is underlined by the fact that the Forum Secretariat is based here. It is also the site of the University of the South Pacific's main campus. The local population is mainly ethnic Fijian but there are Indo-Fijians as well as citizens of Chinese and European extraction. Add to this the diplomatic corps, foreign businesspeople and students from other parts of the region, and you get a very cosmopolitan mix. This is reflected in the variety of cuisines available in the local restaurants.

The western part of Viti Levu is also cosmopolitan but in a very different way, with a stronger Indian influence and, of course, a constantly changing tourist population.

Most of the island's inhabitants live a relatively short distance from the sea. Thus, in demographic terms, Viti Levu is like a doughnut with a thick layer of humanity around the edge and a hole in the middle. The analogy may not be entirely apt since the 'hole' is, in fact, a spectacular mountainous area. This makes the road that runs round the island a key arterial route. Meanwhile, those who choose to fly from Nadi to Suva, assuming they are not of a nervous disosition, can enjoy the experience of travelling below the height of the surrounding peaks.

The few people who do occupy the central region live in traditional Fijian villages and have a lifestyle far removed from either the town dwellers or the sugar cane farmers. Its size may be little more than ten thousand square kiLométres but Viti Levu is truly an island of contrasts.

Fiji-EU cooperation: comprehensive package

by Ernst Kroner

Fiji was a signatory of the first Lomé Convention in 1975 and, to date, the country has been allocated some ECU 190m in EU development cooperation funds.

Starting with a relatively modest ECU 9.9m under Lomé I, the national indicative programme rose to ECU 13m under the following Convention. Without neglecting rural development (feeder roads in Vanua Levu), under Lomé I most of the resources were devoted to transport infrastructure (a main road on Vanua Levu). Under Lomé 11, cooperation concentrated clearly on agriculture and rural development, in particular by means of the funding of microprojects, with infrastructural programmes (the extension of the Vanua Levu road, social infrastructure) taking second place. Under this Convention, a new field of action was also addressed: trade development.

Tax free zone

Trade development was addressed further under Lomé III (6th EDF, ECU 20m, of which ECU 5m in special loans), with support given to an Investment and Trade Development Programme. The longer-term objective of the project was to widen the economic base of Fiji and to create employment. The more immediate objective was the i establishment of a Tax Free Zone near Suva. In order to promote this scheme and to secure markets for exporting the goods which would eventually be produced, the project included a programme of trade and investment promotion to be implemented by the Fiji Trade and Investment Board. Due to problems linked with identifying an appropriate site, the project, which had been given the go-ahead in 1990, only came on stream in 1995.

Rural and agricultural development continued to be one of the main sectors of cooperation, with the funding of three major projects. The first was a coconut rehabilitation and development project, situated on the island of Taveuni, which aimed at improving the productivity of coconut plantations through the introduction and multiplication of high yield hybrids. The project also provided for the establishment of a 30 hectare coconut nursery centre, which was expected to finance itself through the sales of seedlings. EC support for this project ended in 1992, since when the scheme has been taken over by the Government. A second project (a large-scale microprogramme divided into two sub-programmes) aimed on the one hand at the construction of access roads to facilitate the development of cocoa plantations, and on the other at the introduction and development of pineapple plantations in Vanua Levu. The first component was closed after disappointing results. The second component, however, produced very interesting and promising results, which will, however, need private and governmental support in order to become sustainable. A rural electrification project involving 28 rural electrification schemes and the supply and installation of a small power plant is still ongoing.

Developing human resources

Under Lomé III, the formerly prominent transport infrastructure sector lost some importance. The Kubulau Peninsula road project on Vanua Levu brought to an end the work started under previous Conventions. This road, which filled the last gap in the circuminsular road, was opened on in July 1994. Lomé III also saw the beginning of human resources development as a new theme of cooperation, with Technical Assistance funded for the logging school. This area, embodying strong links with forestry and environmental issues, has been further developed under Lomé IV with the reconstruction of the school burnt down in 1993, and the enlargement of the training and education provided to what now constitutes a Forest Training Centre.

The national indicative programme relating to the first protocol of Lomé IV (7th EDF, ECU 22m in grant aid) identifies rural development and social infrastructure as the sectors of concentration to which 65% of resources are to be devoted. The remaining 35% will be used for non-focal activities, including trade and services, tourism, cultural cooperation, training and technical cooperation.

Building bridges

Unfortunately, it was only following the very destructive cyclone Kina in January 1993 that cooperation activities could start in the form of the rebuilding of four bridges either severely damaged or completely destroyed by the post-cyclone floods.

Work on two smaller bridges of major importance to Viti Levu (Korovou and Vunidawa, ECU 1.135m) was started in 1994 by the Public Works Department and completed in January 1995.

The Financing Agreement for the two major bridges (ECU 10.24m) was signed in June 1994 and provides for the rebuilding of the bridges of Ba and Sigatoka. These form part of the main road around the island of Viti Levu and are therefore vital for the movement of people and goods on Fiji's main island. The new bridges, 190 and 182 metres long respectively, will be two-lane, and will provide for footpaths and utilities. To enable the traffic to by-pass the often congested towns of Ba and Sigatoka, new sites for both bridges have been chosen, which also call for the building of new approach roads. Building works were under way in early 1996 and completion is expected by April 1997.

Non programmable aid for Fiji has been considerable over the years. While Stabex transfers for losses on coconut oil (totalling ECU 5.4m under Lomé I - Lomé III) came to a halt under Lomé IV (because levels of exports fell below the required dependency threshold), emergency aid (total ECU 9.5m) has continued, unfortunately, to be needed. Time and again the islands have been hit by cyclones (the most recent occasion being in January 1993, when the EU made available ECU 1 m for food rations following cyclone Kina).

In the past, a significant feature of EU-Fiji cooperation was the credits provided by the European Investment Bank. It was very active under Lomé I to Lomé III, providing loans from its own resources to a total value of ECU 87.5m with a further ECU 6.1 m allocated in risk capital. Loans went to the energy sector (hydropower scheme), industry (wood processing) and services (telecommunications, sea and air transport). Considerable interest rate subsidies (totalling ECU 14.1m) have also been made available under the various EDFs in support of these loans. More recently, the EIB has financed an aircraft maintenance centre (1991) and a telecommunications project (1995).

Trade cooperation

Over and above financial cooperation, Fiji benefits from the second largest quota (165348 tonnes per annum) under the Sugar Protocol annexed to the Lomé Conventions. This covers some 45% of its total sugar exports. The yearly benefit from this provision is estimated at between ECU 45m and ECU 55m - in other words, only slightly less than the total of all programme aid granted since Lomé I (ECU 64.9m). About two-thirds of these benefits reach the farmers, so that the EU subsidises every sugar smallholder, on average, to the extent of some ECU 1500 a year.

Recently, Fiji's quota under the Sugar Protocol was increased by 881 tonnes, as a result of the reallocation of the shortfall of deliveries by Barbados. Furthermore, Fiji benefits from an annual special tariff quota to the tune of some 30 000 tonnes up to the year 2001.

Industrial development and external trade have been supported by the relaxation of the rules of origin for exports to the EU of canned tuna to the extent of 500 tonnes a year from 1993 to 1996. A similar arrangement, applicable for certain quantities of garments up the end of 1993 was recently extended to the end of 1996.

Fiji's main exports to the EU (sugar, fish and garments) - and the resulting surplus in its trade relations with the EU - are consequently highly dependent upon the continuity of these preferences.

Support for tourism

In the field of services, and specifically in tourism, the EU - through its support of the Tourism Council of the South Pacific - has contributed to the fact that every sixth tourist or so arriving in Fiji comes from a member country of the Union. Tourism being by far Fiji's most important source of foreign exchange earnings, receipts from European tourists amount at present to some ECU 30m, and are greater than those from the export of fish and fish products

Taking the Sugar Protocol into consideration, the EU is by far the most important of Fiji's development partners, followed by Australia. The country also benefits from bilateral cooperation arrangements with EU Member States (UK, France, Germany).